The incredible story of the 116kg, 125hp homemade Chevallier GP machine taken to 7th in the World 500cc Championship by Didier de Radiguès... Test: Alan Cathcart Photography: Kel Edge

To defeat the Japanese teams by winning GPs with bikes you built yourself in a workshop attached to your house, fuelled by your wife’s home cooking and cups of coffee freshly brewed in the kitchen next door, is a quixotic achievement that’d be impossible today.

But in the early 1980s that’s exactly what French engineer Alain Chevallier succeeded in doing, and his death from cancer in October 2016 aged 68 saw us losing one of the great chassis designers of modern day GP history.

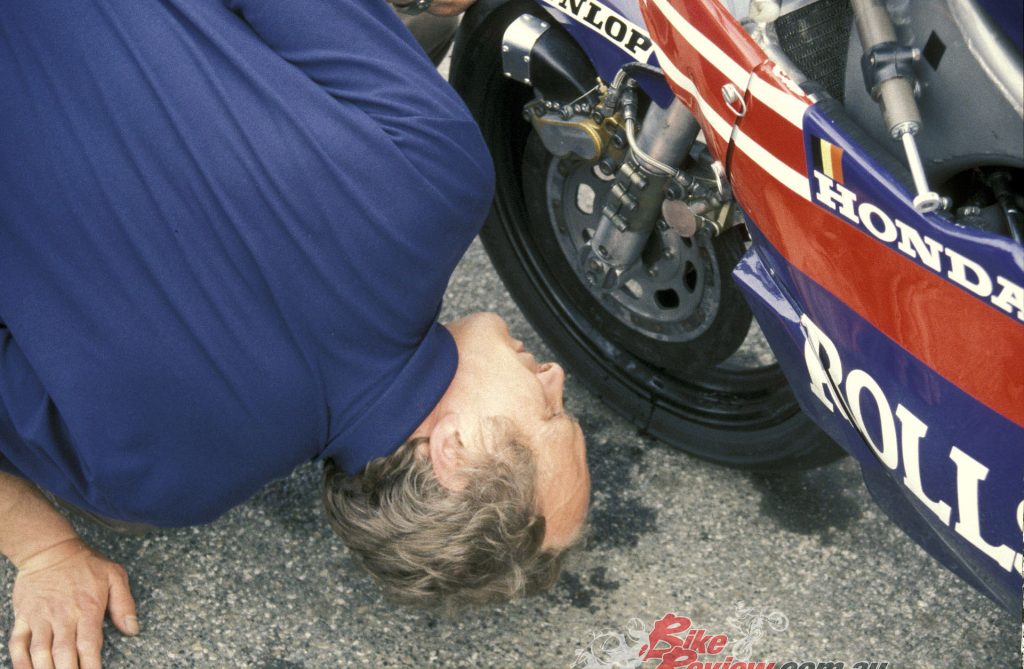

When as powerful a figure as HRC boss Youichi Oguma lent factory engines to Alain Chevallier’s small team, it was a mark of respect for what his bikes had achieved against all odds, on a limited budget. While the Japanese were following Antonio Cobas in building aluminium chassis, Chevallier maintained his allegiance to tubular steel frames – but using cold-drawn steel which, being 20 per cent stronger than hot-rolled, offers an increased stiffness to weight ratio, plus improved rider feedback. Ducati would follow in his tyre tracks later that decade en route to successive World Superbike titles with its tube-framed racers, and eventually of course to the 2007 MotoGP World title.

But Alain Chevallier didn’t stop there. As part of his drive to save weight to compensate for the less powerful customer engines in his bikes, he was the first to fit carbon disc brakes to a 500GP motorcycle, and the first to feature ram air induction and a still air box on his GP bikes. He was a pioneer in developing fully adjustable suspension, too, making his own forks and shocks, as well as in telemetry. The Chevallier workshop was a hotbed of innovation.

The first to fit carbon disc brakes to a 500GP and the first to feature ram air induction

Alain Chevallier’s younger brother Olivier had become a top bike racer, winning the 1976 350cc Yugoslavian GP with a bike prepared by Alain as chief mechanic for the Pernod-funded team. By 1980 he’d started making his own Yamaha TZ250/350-powered bikes for Olivier to race – but that April Olivier was tragically killed at Paul Ricard on a TZ750.

The distraught Alain was set to turn his back on racing, before his friend Eric Saul persuaded him otherwise. Just six weeks after Olivier’s passing, Saul put a Chevallier Yamaha on the rostrum for the first time in the 350cc French GP at Ricard, repeating that third place finish at Silverstone later that year to finish sixth in the final points table.

“We had an excellent season with lots of pole positions and fewer crashes, but we just didn’t quite have enough to win the title,” Alain Chevallier.

Despite his brother’s death, Alain Chevallier continued to build and race motorcycles. In 1982, Belgium’s Didier de Radiguès rode a Chevallier Yamaha to victory in the 350cc Yugoslavian GP, to wind up second in the World Championship. Teammate Eric Saul won the Austrian GP and finished the championship in fourth. For 1983, now with ELF sponsorship, Didier was joined in the 250GP Chevallier team by Jean-François Baldé, and the dream result of the first race at Kyalami saw victory on his Chevallier debut for the Frenchman, with de Radiguès second.

cold-drawn steel, being 20 per cent stronger than hot-rolled, offers an increased stiffness to weight ratio

But Baldé broke his leg at Assen, and despite pleasing his local Johnson cigarette sponsors with victory in the Belgian GP at Spa, Didier could only finish third in the World Championship, behind Yamaha factory riders Carlos Lavado and Christian Sarron. “We had an excellent season with lots of pole positions and fewer crashes, but we just didn’t quite have enough to win the title,” Alain once told me. “But for 1984 we started a new adventure.”

Indeed so – for with the demise of the 350cc class, and already accustomed to racing in two gruelling GP races in a single day, alongside his 250GP ride in 1983 Didier de Radiguès had begun a 500GP career with a stock Honda RS500, one of 32 customer replicas of the NS500 triple which Freddie Spencer had turned into a 1982 GP winner.

But the Honda’s flawed handling was a disappointment, so for 1984 Didier convinced Alain Chevallier to move up to the 500cc class with an all-new bike using the Honda RS500 V3 engine, with sponsorship from ELF and Johnson, and to run a backup bike for Christian Le Liard.

Didier de Radigues splashing his way to an impressive fourth place at the 1984 South African Grand Prix, Kyalami. It was their first race and he had led the early laps. Amazing… Le Liard was eighth place so two top ten finishers.

The tube-frame Chevallier Honda RS500 was tested at a wintry Paul Ricard by Didier, who declared it to be ‘right first time’! He then proved that by leading the first four laps of the bike’s very first race a month later in the opening South African GP, before finishing fourth with teammate Le Liard eighth. With three other top ten finishes the Belgian finished ninth in the World Championship, a satisfying result for him and Chevallier. But strangely, though, not for ELF, which for 1985 supported Serge Rosset’s team instead. Politics!

Redesigning Pernod’s own 250GP bike gave the four full-time Chevallier employees something to do in 1985, while the ex-de Radiguès 500 was lent to French privateer Thierry Espié, who scored points on it twice before returning it to Alain. Meantime, the other ex-Le Liard bike was twice tested by Randy Mamola, anxious to redress the handling issues he was experiencing with his factory NS500 triple.

Highlight of the year was a magnificent second place for Didier on the Chevallier Honda triple in the pouring rain at Silverstone

While expressing satisfaction with the French bike he never raced it in the end, though HRC boss Youichi Oguma allowed teammate Takazumi Katayama to race a Bakker-framed such bike – whereupon Honda replicated the Dutch chassis design for their 1985 Mark 2 version! It might have been a Chevalier ripoff, instead…

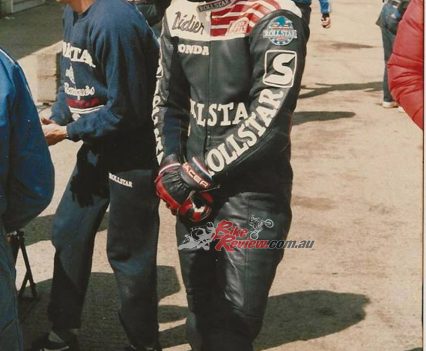

For 1986 the Rollstar Chevallier team was formed with de Radigues finishing seventh in the 500cc World Title.

For 1986 the de Radiguès/Chevallier/Honda RS500 lineup was re-formed with Rollstar sponsorship, resulting in an even more successful season with eight top ten finishes in the 12 races, en route to seventh place in the World Championship – and top Honda triple, two places ahead of Ron Haslam on the Rosset-run ELF 3!

Highlight of the year was a magnificent second place for Didier on the Chevallier Honda triple in the pouring rain at Silverstone in 1986 (see video above), just nine seconds behind winner Wayne Gardner’s NSR500 V4 Honda, and ahead of all the other factory four-cylinder bikes, including third place finisher (and that year’s future World champion), Eddie Lawson’s Yamaha.

For 1987 de Radiguès was hired by Cagiva with Chevallier as chassis consultant, scoring the best finish yet for the Italian factory with 4th place in Brazil. But tensions within the team saw Alain turn away from GP racing altogether, despite the offer of Honda NSR500 factory engines from Oguma-san which he had to decline, with no team to run the putative V4 Chevallier Honda.

Find Alan’s rides on the RGV500, YZR500 , TZ750 and Jeff’s ride on the Cagiva 500 here...

He instead began working for Sonauto Yamaha, developing their Paris-Dakar bikes and working on the hub-centre Yamaha GTS road bike that debuted in 1993. A year later, he began a new job as Technical Director of France’s newly formed Voxan motorcycle company, having been recruited by owner Jacques Gardette to design the chassis and oversee technical development of the bikes.

In only two seasons, 1984 and 1986, the Chevallier 500 made an enormous impact. Alain turned his back on GP racing from 1988, moving to develop Paris Dakar Yamaha’s and the hub-steering Yamaha GTS1000! What a guy…

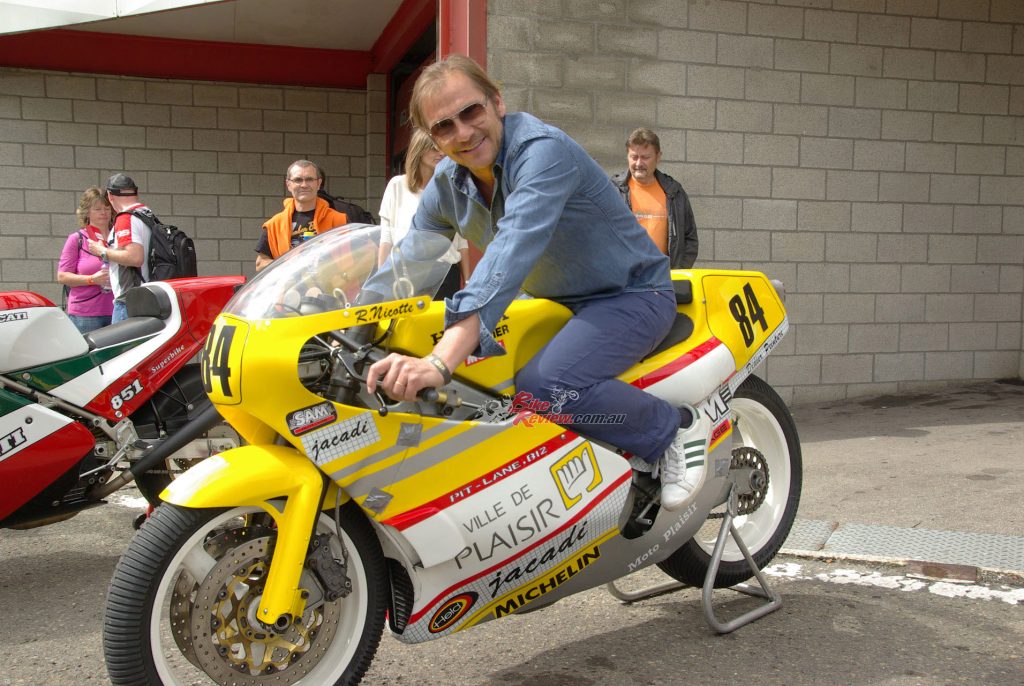

Just three Chevallier Honda RS500 triples were built – the initial 1984 de Radiguès/Johnson bike, the Le Liard/ELF one copied from it, and the third Rollstar one built new in 1986, with altered chassis geometry and the potential to adjust this via eccentrics. The original 1984 Johnson bike was used as a backup in ‘86, but in 1988 Chevallier sold this to French privateer Rachel Nicotte, who won the French 500cc National title with it that year, scoring victory in most of the races, sponsored by Jacadi, a childrens’ clothing manufacturer for whom the French series was the main priority.

Nicotte also managed to fit in seven 500GP starts between the rounds, finishing in five of these, and in Jerez he scored three World Championship points with a 13th place. In 1989 he contested the European Championship, finishing second in the series, with just three GPs squeezed in between these rounds.

For 1990 money was short, so Nicotte only started three 500GPs, twice finishing in the points. Thereafter, he switched to more affordable 600 Supersport racing, in which he twice became French champion, as well as twice winning the Le Mans 24 Hours – first in 1992 on a privateer Yamaha, and a second time in 1995 on a factory Honda RC45. Sadly he passed away in 2005 aged just 48-years.

The Chevallier workshop was a hotbed of innovation.

The coordinator of Nicotte’s small Chevallier Honda 500GP team had been his neighbour in Plaisir – the town Rachel lived in outside Paris – Olivier ‘Gull’ Rietsch. Gull owns the ex-de Radiguès, ex-Espié, ex-Nicotte bike today, still painted in the Ville de Plaisir colours in which Nicotte ran it in 1989-90, sponsored by his home town, whose Mayor must have been a bike fan!

Gull owns the ex-de Radiguès, ex-Espié, ex-Nicotte bike today, still painted in the Ville de Plaisir colours in which Nicotte ran it in 1989-90.

“I gave up my job in property maintenance to go racing with Rachel in 1988,” recalls Gull, today living in French Guyana with occasional returns to France to drink rum with his racing friends! “I did everything that didn’t involve working on the bike or riding it – so that meant driving the truck, keeping us fed, sourcing fuel, parts, supplies and tyres, and especially repairing bodywork – Rachel used to crash a lot. I mean – a LOT! We ran it literally on a shoestring, because we had no money for parts. We made friends with one of the Honda mechanics, and he’d tell us ‘At exactly 9pm this evening, I’m going to throw our worn out parts in that bin over there,’ so we made sure to be waiting around the corner then. Their idea of worn out was simply nicely run in for us!”

After Nicotte stopped racing the Chevallier, he entrusted it to Gull for safe keeping, until Gull eventually bought the bike from him. “It had been part of my youth – I’d lived three whole years of my life centred around that bike, so it wasn’t going anywhere else.” Nicotte’s tragic passing in 2005 inspired Gull to have the bike rebuilt to run again in the increasingly numerous Historic events like the Bikers Classic at Spa. It was at the 2014 edition of this that we found ourselves sharing a pit and, well – you can guess the rest.

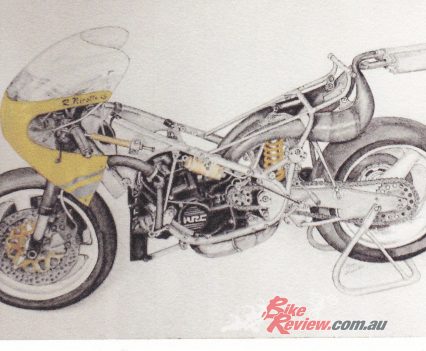

The fully adjustable 40mm Chevallier upside down fork – complete with one set of internals stamped ‘Chevy’ and the other ‘CAG 500’! – is set at a steeper 23° rake than the stock Honda’s 24.5.

However, my promised test ride on the bike had to wait five years more while Gull managed to source some new pistons for the V3 Honda engine. Finally, in 2018 a batch was made by Tech 3 Classic in between racing a satellite KTM in MotoGP, allowing Gull’s mate Emmanuel Laurentz to rebuild the engine, while French classic race guru Yves Kerlo undertook a frame-up restoration which was completed just a fortnight before the fabulous 2019 Sunday Ride Classic at Paul Ricard in May.

There, in the first couple of sessions, I found myself running-in the newly rebuilt motor with the likes of Freddie Spencer, Kevin Schwantz, Giacomo Agostini (and his son Giacomino!), and Christian Sarron zapping past me as I bedded in those new pistons. Well, that was my excuse, anyway….

“You’re immediately aware of how ‘reet petite’ the Chevallier is when you ride it – as against the dozen-odd NS/RS500 Honda triples I’ve been fortunate to ride down the years”.

The Johnson Chevallier features Alain’s distinctive cold-drawn tubular steel twin-loop frame, with massive strengthening around the steering head, despite which it only weighs just over 5kg, minus the fabricated chrome-moly tubular steel swingarm with fully adjustable White Power monoshock and variable-rate link.

The fully adjustable 40mm Chevallier upside down fork – complete with one set of internals stamped ‘Chevy’ and the other ‘CAG 500’! – is set at a steeper 23° rake than the stock Honda’s 24.5°, whereas at 1420mm the wheelbase is much longer that the RS500’s 1375mm – presumably for added stability.

However, instead of the single carbon front disc, which de Radiguès raced with in 1984, there’s a pair of 310mm AP-Lockheed steel discs fitted today, with four-piston calipers. That’s because the impecunious Thierry Espié fitted these when he borrowed the bike for the 1985 season – he couldn’t afford to replace the carbon discs regularly when they wore out, so they’ve been there ever since!

This means that the bike today weighs 116kg dry, rather than the 111kg it scaled in 1984 – but with a 52/48% forward weight bias even with the forward-facing array of carbs, which resolved the stock RS500’s problems of insufficient weight on the front wheel.

The bike is 116kg dry now, rather than the 111kg it scaled in 1984 – but with a 52/48% forward weight bias.

However, you’re immediately aware of how ‘reet petite’ the Chevallier is when you ride it – as against the dozen-odd NS/RS500 Honda triples I’ve been fortunate to ride down the years, this is a 350 compared to a 500. In fact, Rachel Nicotte was much shorter than me, so I found the close-coupled riding position much too cramped to feel comfortable on the Chevallier – I couldn’t move around on the bike very easily, and it was impossible to tuck my head behind the screen. That was a pity, as Didier de Radiguès and I are the same height, and it would have been nice to try it as he rode it.

“The Chevallier was super stable in fast sweepers, like the fourth-gear Signes right-hander at the end of the Mistral Straight, where that longer wheelbase surely came into play”.

But what this meant was that I got a great sense of the bike’s flickability, the way I could swap direction on it so relatively easily in Paul Ricard’s copious chicanes, without hanging off. But the Chevallier was super stable in fast sweepers, like the fourth-gear Signes right-hander at the end of the Mistral Straight, where that longer wheelbase surely came into play, compensating for the tight steering geometry. It wasn’t remotely nervous-steering or twitchy, just felt planted with a heaps of security.

But it also braked well, with its light weight surely a factor as I found in a fascinating ‘battle’ on the Sunday main event at Ricard with Eric Beurlys on a standard Honda RS500 triple. Thanks to the Chevallier’s light weight and the ultra-effective AP-Lockheed brake package, I could gain many yards on him braking into the chicanes, or the tight right-hander after Signes – but then he’d get on the gas harder than me exiting the bend and pull those yards back, where I was constrained by the 11,000rpm ceiling I’d been asked to observe while those new Tech 3 pistons bedded in.

Tantalisingly, that was just when the Honda engine wanted to really take off, after coming on strongly from 9,500 rpm upwards quite fiercely, without the absent ATAC powervalves fitted to the works Honda triples and later customer bikes, which helped smooth out power delivery on those so well.

“What a sweet little motorcycle – well, not so little, with 125bhp delivered at 11,500 rpm: call it a bike that punched above its weight”.

But for my last four laps on the bike I revved it out to 11,800 rpm in the gears, and it made a huge difference to the Honda’s acceleration, as well as making it much easier to ride. That’s because it was now snicking nicely all through the gears on the one-up race-pattern left-foot gearshift to leave me still in the powerband as I hit each higher ratio, instead of having to work the light-action clutch to coax it back on the pipe.

Yet the greater torque this also accessed didn’t upset the sense of balance from the Chevallier frame, and the easy way it steered. What a sweet little motorcycle – well, not so little, with 125bhp delivered at 11,500 rpm: call it a bike that punched above its weight.

Left to Right; Olivier Rietsch, Yves Kerlo, Emmanual Laurentz, Christian Quinquenel and Youri Chalumeau.

The only pity is that Alain Chevallier is no longer with us, so he can’t admire the wonderful job that Gull & Co. have achieved in restoring the Chevallier Honda 500 mother ship. Kudos, Gull – and thank you!

1984 Chevallier Honda RS500 Specifications

1984 Chevallier Honda RS500 Specifications

Engine: Water-cooled reed-valve single-crankshaft 90o V3 two-stroke, 62.6 x 54mm bore x stroke, 499cc, 3 x 34mm Keihin carburettors, Kokusan-Denko CDI ignition, 6-speed extractable cassette-type gearbox, multiplate dry (7 friction/7 steel) dry clutch, 125bhp@11,500rpm.

Chassis: Cold-drawn chrome-moly tubular steel twin-loop frame, fully adjustable 40mm Chevallier inverted telescopic forks, fabricated chrome-moly tubular steel swingarm with fully adjustable White Power monoshock and variable-rate link, 23 degrees rake, 1420mm wheelbase, 52/48 % weight distribution, 2 x 310mm steel rotors with four-piston AP-Lockheed calipers (f), 1 x 220mm steel rotor with two-piston Brembo caliper (r), 120/70-17 Pirelli Diablo on 3.50 in. Marvic cast magnesium wheel (f), 180/55-17 Pirelli Diablo Superbike on 5.00 in. Marvic cast magnesium wheel (r).

Weight: 116kg dry (as tested – 111kg with single carbon front brake disc)

Top speed: Over 280km/h

Year of construction: 1984

Owner: Olivier Rietsch, Saint Laurent du Maroni, French Guyana

Interview: Didier de Radigues – Alan Cathcart

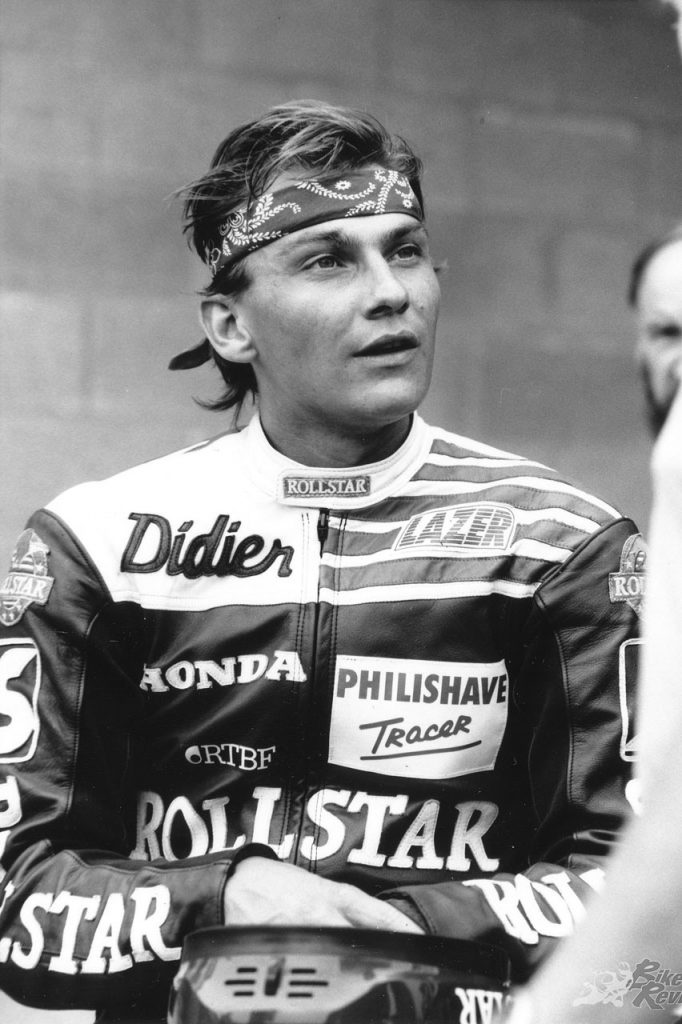

Didier de Radiguès is the most successful Belgian GP racer ever, with four race wins, as well as 15 rostrum finishes spread between the 250, 350 and 500cc classes – all but two on bikes built by Alain Chevallier, with whom he enjoyed a long collaboration…

“In the close season between the 1983 and ‘84 seasons Alain and I decided we were going to try to compete in 500GP racing with our own bike. I’d narrowly missed out on the 250GP title in 1983 because we were a very small team, and so some stupid parts would break, and things like that. So we decided we preferred to miss winning the title in 500GP rather than in 250/350GP, because then we’d be competing at the highest level against the top Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki factories with our self-built bike! It would be even more difficult for us to beat them, because they’d would always have more money and experience, but we were ready to try. So we bought an RS500 Honda, and we took the chassis and put it in the loft. Chevallier then built his own tubular steel frame, which we tested in Paul Ricard in February 1984 as the basis for future development.”

“I’d already ridden a few GPs the previous year with a standard Honda RS500, which allowed me to discover the faults in the bike, particularly the lack of weight on the front wheel. I really didn’t like this RS production bike at all, because it was completely different to what I was used to, namely the sweet-handling Chevalliers – it seemed you could do anything you liked with Alain’s bikes. But we knew the Honda engine was OK, so we just had to work on the chassis, and that’s what we did. This first chassis Alain had made was supposed to be just a base-level design, which would then be changed as development proceeded. But I liked it so much the first time I rode it at Paul Ricard, we continued racing it all through the 1984 season. Alain later built another one, but in the end, to the same design. He got it right first time! That was proved by my result in the bike’s very first race just one month after riding it for the first time – I finished fourth at Kyalami in spite of losing so much speed down the long front straight compared to the four-cylinder bikes.”

“We didn’t have the same horsepower as the factory triples – ours was an RS engine, not an NS, and it wasn’t a four-cylinder, either, which that year Honda started racing themselves. So we decided to work on the weight, and to focus on reaching the minimum weight limit if at all possible. This also meant using carbon brakes, to begin with because they were lighter than steel discs, then only later because they worked better, too, which allowed us to use only one front disc. So for sure in 1984 we were the first ones to use carbon brakes, and it was very difficult at first, and we had many problems. It was only a very small company that made them, so Chevallier was designing the discs, the pads, the air intake, everything. We had a lot of trouble with overheating, because the carbon disc was getting too hot, so we had to put air ducts onto it to try to get the right temperature for the brakes. I remember at Anderstorp I couldn’t finish the race because my disc got too hot, and after only ten laps I had no more brakes! But the Chevallier was more stable and had more front grip than the factory Honda triples, and so we had more turn speed, too. It was a good first year with the bike in 1984, and I finished ninth in the World Championship with it.”

“For 1985 a big mistake happened, and because ELF asked me and it was an important sponsor for me I went to ride a standard Honda-3 with Serge Rosset’s team. I had a very consistent season and finished eighth in the championship with just two DNFs and a fourth place at Silverstone – but it just wasn’t such a nice bike to ride, and so for 1986 I came back to Chevallier, this time with Rollstar sponsorship.”

“For 1985 a big mistake happened, and because ELF asked me and it was an important sponsor for me I went to ride a standard Honda-3 with Serge Rosset’s team. I had a very consistent season and finished eighth in the championship with just two DNFs and a fourth place at Silverstone – but it just wasn’t such a nice bike to ride, and so for 1986 I came back to Chevallier, this time with Rollstar sponsorship.”

“In 1986 I rode a similar bike for Chevallier as in ’84, but it for sure it had moved forward, and we had a great season. We always wanted to try something different because we were competing against the factories, so that year we went with Dunlop for tyres, and we worked a lot with them. We tried new tyres all season long, sometimes bad, sometimes good, but thanks to them we could do a lot more testing. We didn’t have enough money to do that ourselves, but they were paying for it, which helped us refine the bike even more. I had some good results that year with second in the British GP, which was great, and several top ten places, always against factory bikes. The Chevallier was very light, and a very little, compact bike that for some reason was especially good in qualifying and at the beginning of the races – I don’t know why. I think it was a great achievement for such a small team to finish seventh in the championship, ahead of all the other three-cylinder Hondas.”

“But we never had enough money, so because we wanted to go higher, Chevallier and I accepted a proposal from Cagiva. Claudio Castiglioni wanted me to go there, but I said, “I’ll agree, but only with Chevallier.”. Although at that time Cagiva was nowhere, we decided – OK, there we will have the money, for sure! Francis Batta was team manager, and Chevallier was the engineer, and we had sponsorship from Belga cigarettes, so it was a proper Belgian-Italian team. But it was very difficult because Castiglioni was not very receptive to Chevallier, and there was not very friendly competition inside the team with Cagiva Normale against Cagiva Chevallier. And so that was quite awkward! But the bike kept getting better all through the season, largely thanks to Alain, and I finished fourth in the Brazilian GP at the end of the season, which was the best ever result for Cagiva at that time. But the following season my collaboration with Alain ended when I moved to Yamaha – it had been a great few years together, in which I think we worked very well as a team, and each learnt things from the other.”